Global Environmental Sessions and Their Reach

UN environmental sessions such as the UN Environment Assembly (UNEA), the annual Climate Change Conferences (COP), and the negotiations for the High Seas Biodiversity Treaty are where global environmental standards are set. These forums do not merely produce statements; they create frameworks that shape national policy, financing flows and the expectations of private sector actors.

Policy Alignment and Legal Obligations

Resolutions and agreements emerging from these sessions typically require participating countries to align their domestic laws. For Sri Lanka this has meant:

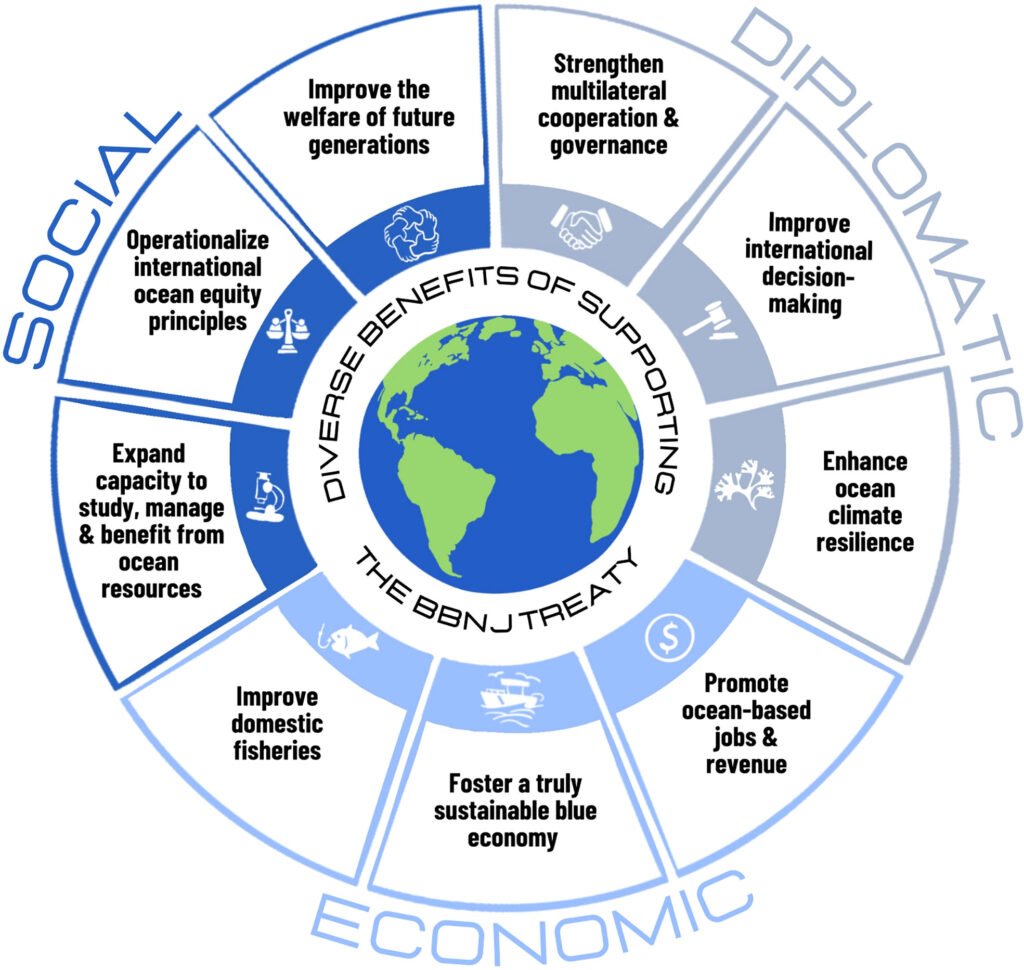

- Preparing to implement the High Seas Treaty (BBNJ Agreement), which mandates the protection of marine biodiversity in areas beyond national jurisdiction.

- Committing to long-term climate goals such as a coal phase-out by 2040 and net-zero emissions by 2050, as declared in recent UN General Assembly interventions.

- These commitments demand new legislation or amendments to existing statutes, for example tighter environmental impact assessment rules and more stringent coastal zone regulations.

Access to Finance and Technical Assistance

UN sessions are a gateway to global green finance and technical support. UNEA decisions determine the United Nations Environment Programme’s budgets and strategy; climate conferences set the direction for funds such as the Green Climate Fund and Loss & Damage finance mechanisms. For Sri Lanka, participation translates into eligibility for concessional finance to expand renewable energy, strengthen disaster resilience and improve waste management. Without active engagement, securing these funds becomes more difficult.

Diplomatic Leverage and International Standing

By participating and negotiating at these sessions, Sri Lanka enhances its diplomatic profile. Strong involvement helps Colombo gain leverage in bilateral and multilateral negotiations, including trade and investment deals where environmental standards increasingly matter. A visible commitment to global environmental goals also strengthens the country’s case when seeking international assistance after climate-related disasters.

Read the latest analysis on “Singapore-Based Operator Refuses to Pay X-Press Pearl Damages“.

Norm-Setting and Soft Power

UN resolutions often operate as “soft law”: even when non-binding they set norms that influence national policy and corporate behaviour. Peer pressure and the risk of reputational damage create incentives for compliance. For example, after COP28 the UN called on Sri Lanka to accelerate sustainable practices, reinforcing internal pressure from civil society and the private sector to move faster on renewable energy and circular-economy initiatives.

Domestic Policy and Stakeholder Mobilisation

Outputs from UN sessions provide civil society and media with a global benchmark. NGOs and advocacy groups can use these commitments to lobby for stronger domestic legislation. Provincial authorities and line ministries can point to international obligations when arguing for budget allocations or tougher regulations on polluters. The result is an internal policy dialogue driven by external commitments.

Economic and Sectoral Effects

- Energy: Transition targets drive investment in solar, wind and grid upgrades, but also require upfront capital and policy consistency.

- Fisheries and Marine Resources: Implementation of the High Seas Treaty and related ocean-protection commitments could introduce stricter rules on offshore fishing and shipping, affecting commercial fleets but opening opportunities for sustainable aquaculture.

- Tourism: Eco-tourism gains from stronger environmental stewardship, but operators must meet higher standards in waste management and emissions reporting.

- Industry and Infrastructure: New emissions caps or pollution standards raise compliance costs, but create markets for environmental technology and services.

Challenges and Constraints

Sri Lanka’s capacity to meet these obligations is limited by fiscal constraints and uneven institutional strength. Even when UN sessions promise financing, disbursement can be slow or tied to reforms that require political consensus. Some domestic actors view UN mandates as encroaching on national sovereignty, creating political resistance. Translating global norms into local regulations requires careful balancing of economic development and environmental protection.

Outlook

UN environmental sessions are more than symbolic gatherings. They are a mechanism through which global norms, finance and technology transfer reach national economies. For Sri Lanka, active engagement can bring green finance, technical expertise and diplomatic influence. Yet the benefits depend on credible implementation at home: passing the necessary laws, enforcing regulations and investing in institutional capacity. Without those steps, commitments made in New York, Nairobi or Dubai risk remaining aspirational, and the economic opportunities tied to them will be missed.

Summary of UN Environmental Sessions

UN environmental sessions influence Sri Lanka through five main channels: binding or persuasive international obligations, access to finance and technical assistance, diplomatic leverage, soft power norms and domestic mobilisation. The net effect is to pull Sri Lanka’s environmental policy and by extension key economic sectors into closer alignment with global standards. The challenge is to convert these global commitments into tangible local action without overstraining already limited fiscal and institutional resources.

___________________________________________________________

Read “Balancing Development and Conservation: The Future of Sri Lanka’s Coastal Ecosystems“, here.

Read “CEB Restructuring: A Turning Point for Sri Lanka’s Power Sector“, here.