Sri Lanka’s fiscal crisis has forced a difficult debate: how to balance essential public services with the need to cut spending and stabilise debt. In its Public Finance Review 2025, the World Bank urges the government to “trim” the public sector, not through sudden layoffs, but through a careful process of rightsizing and efficiency reforms.

This is not an austerity mantra. The Bank’s proposals aim to protect health, education and core government functions while restoring fiscal credibility. The challenge is to reshape a state that has grown large and costly without eroding public trust.

Why the World Bank Is Calling for Change

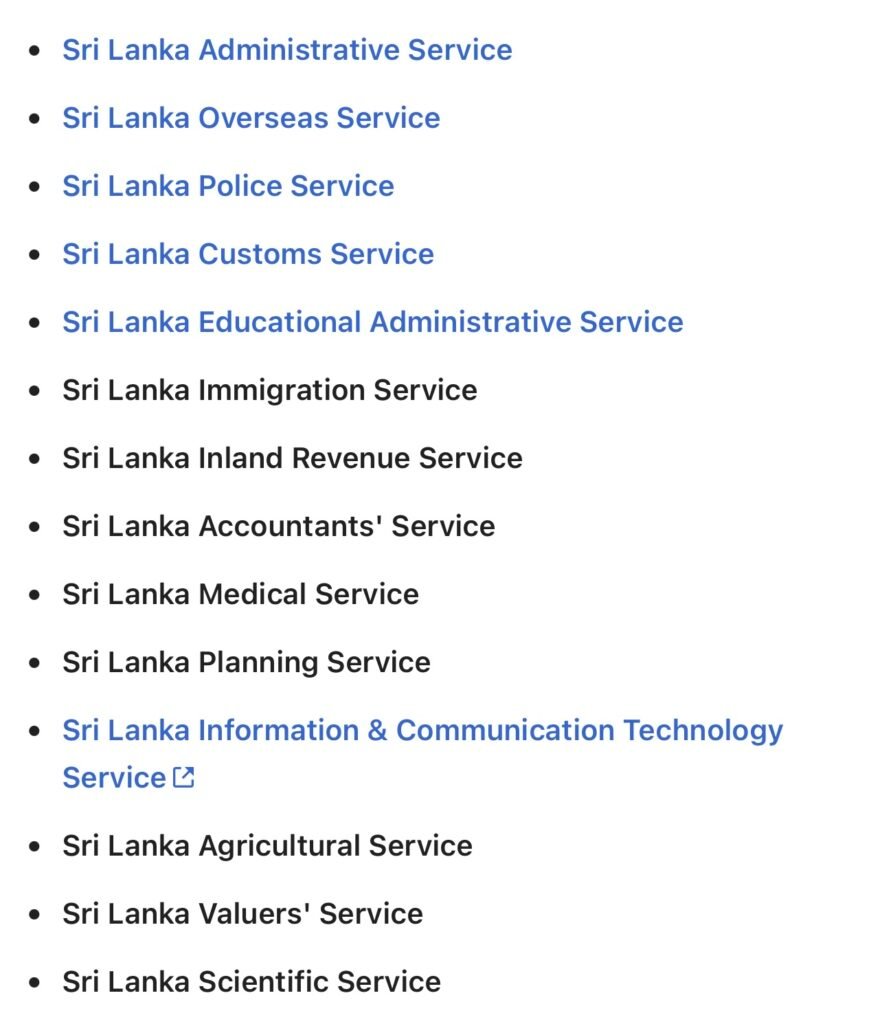

Sri Lanka’s public service around 1.4 million employees absorbs a significant share of government spending. After the 2022 debt default and record inflation, wages and pensions became a heavy burden. Revenue recovery has been slower than expected and the country must meet International Monetary Fund (IMF) programme targets. The Bank argues that better management of the public payroll is essential for long-term fiscal health.

Key Recommendations

1. Gradual Rightsizing via Attrition

The Bank advises reducing headcount naturally as staff retire, while slowing new recruitment. This avoids mass redundancies and preserves institutional knowledge.

2. Comprehensive Functional Review

Each ministry and agency should identify which functions are essential, which can be merged and which are redundant. Only after such an audit can staff needs be re-defined.

3. Integrated HR and Payroll Data

Fragmented payroll systems hide inefficiencies. A single digital HR platform would allow better tracking of wages, overtime and vacancies and reduce “ghost” employees.

4. Protect Frontline Services

Health workers, teachers and security services must be shielded from indiscriminate cuts. Essential services remain the state’s core responsibility.

5. Simplify Pay Structures and Safeguard Real Wages

Decades of ad-hoc allowances have created an opaque pay system. The Bank recommends a simpler salary grid and regular cost-of-living adjustments to maintain morale.

6. Re-prioritise Capital Investment

Instead of launching new large projects, complete those already under way and focus on maintenance. This yields better returns and prevents further fiscal stress.

7. Strengthen Tax Mobilisation

Alongside cost controls, Sri Lanka must raise revenue by expanding the tax base, limiting exemptions and digitising tax administration.

Read the article on “AI in Sri Lanka’s Financial Sector: What the Central Bank’s Signal Means“

Risks and Trade-Offs

Reform is not risk-free.

- Service delivery gaps: Rapid attrition can leave schools and hospitals understaffed.

- Political resistance: Public employees are a strong voting bloc; unions may oppose changes.

- Morale and corruption risks: If wages lag behind inflation, staff may disengage or seek illicit income.

- Regional inequality: Rural areas could suffer if cuts are applied uniformly.

- Short-term economic drag: Lower public payroll spending may dampen domestic demand.

These risks mean reforms must be phased and transparent.

Lessons from Other Countries

Countries from Ghana to Greece have restructured their public sectors. Common success factors:

- Phased implementation with clear timelines and periodic review.

- Transparent criteria for identifying redundant functions.

- Protection of frontline services and vulnerable workers.

- Voluntary retirement or retraining schemes rather than compulsory layoffs.

- Robust data systems to monitor progress and curb payroll fraud.

Implications for Ceylon Public Affairs

Policy institutes, media and civil society have a vital role:

- Oversight: Track whether reforms protect service quality and regional equity.

- Research: Model how different staffing scenarios affect health, education and economic growth.

- Public communication: Explain to citizens that rightsizing targets efficiency, not indiscriminate austerity.

- Labour dialogue: Encourage negotiation and retraining pathways to reduce conflict.

- Legal reform: Strengthen the mandate of the Management Services Department and audit institutions to enforce new staffing norms.

The Way Forward

Sri Lanka can move from crisis management to long-term stability if it:

- Publishes a full functional review of ministries and departments.

- Defines and ring-fences essential services.

- Implements a unified HR and payroll system within two years.

- Phases staff reductions over three to five years via natural attrition.

- Offers voluntary retirement and re-training where needed.

- Simplifies the pay grid while maintaining cost-of-living adjustments.

- Broadens the tax base to reduce dependence on debt.

These steps demand political courage and careful sequencing. Failure would risk another fiscal breakdown; success would create a leaner, more capable state.

Conclusion

The World Bank’s call to “trim” Sri Lanka’s public sector is ultimately about creating a sustainable, efficient government. If carried out with care, it could protect essential services and strengthen public finances. If rushed or politicised, it could deepen inequality and trigger social unrest. The stakes for policymakers—and for every citizen—are high.

Check for more updates – ceylonpublicaffairs.com