After one of the deepest economic crises in its post-independence history, Sri Lanka is now entering a fragile phase of recovery. Inflation has cooled, foreign reserves have stabilised, and GDP growth has returned to positive territory. But beneath the surface, structural vulnerabilities remain. The question is no longer whether the country has survived the worst it’s whether it can build a foundation strong enough to sustain real, inclusive growth.

From Collapse to Stabilisation

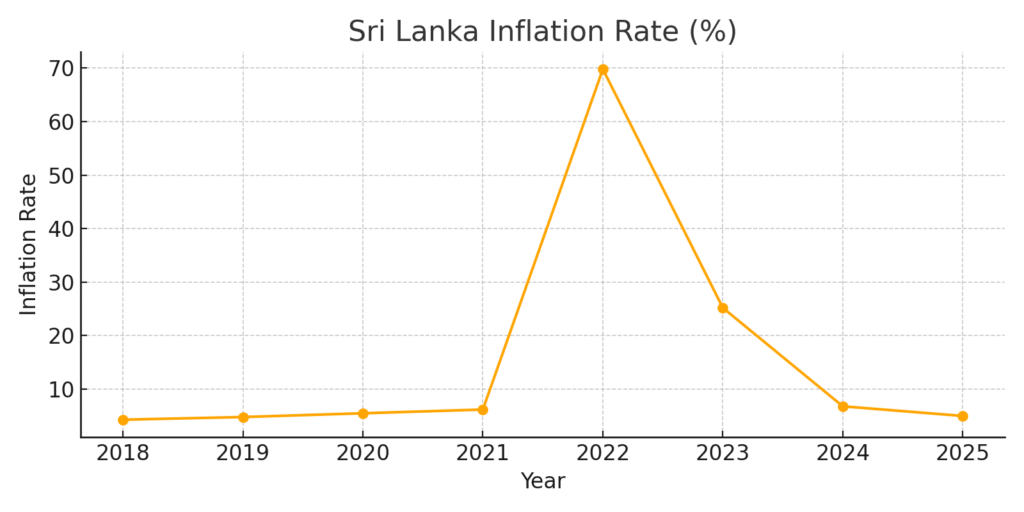

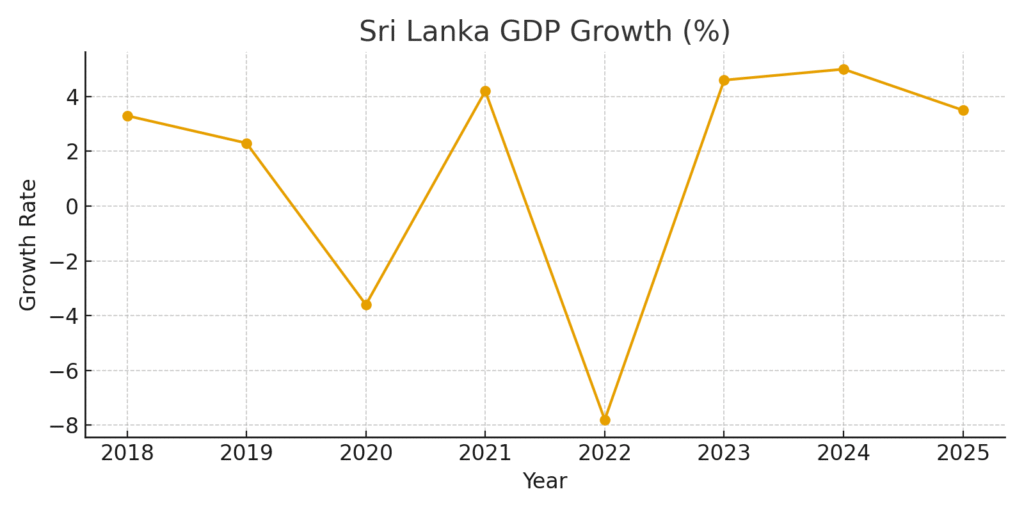

The crisis of 2022–2023 was marked by runaway inflation, sovereign default, fuel and medicine shortages, and widespread social unrest. Inflation peaked at nearly 70%, while GDP contracted sharply, exposing years of fiscal mismanagement and external overdependence. Since then, the government has implemented a series of reforms under IMF guidance: restructuring debt, rationalising subsidies, tightening monetary policy, and improving revenue collection.

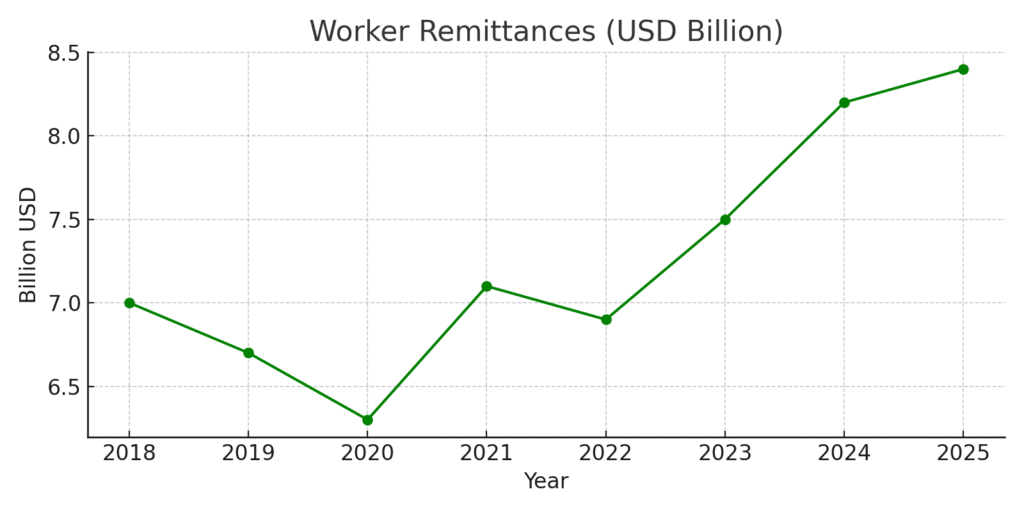

By 2025, inflation has dropped below 10%, and GDP growth has rebounded to over 4%. Worker remittances have climbed steadily, reaching nearly USD 8.8 billion, and tourism has begun to recover, injecting much-needed foreign exchange into the system. These are signs of progress but they are not guarantees of resilience.

The Structural Fault Lines

Despite the macro improvements, Sri Lanka’s economy remains exposed to several persistent risks:

- Debt sustainability: While restructuring has eased short-term pressure, long-term solvency depends on maintaining primary surpluses and reforming state-owned enterprises. Without discipline, the debt stock could rebuild quickly.

- Revenue fragility: Tax buoyancy has improved, but much of it is driven by cyclical factors like vehicle imports and rupee depreciation. A broader, more predictable tax base is essential to avoid future shocks.

- Energy and logistics costs: Fuel and electricity tariffs remain volatile, and inefficiencies in transport and cold chain logistics continue to inflate food prices and reduce competitiveness.

- Labour market mismatch: Youth unemployment and underemployment persist, especially in rural areas. Without targeted skilling and private sector expansion, the demographic dividend will remain untapped.

- Tourism volatility: While arrivals are rising, the sector remains vulnerable to global shocks, regional competition, and domestic infrastructure gaps.

The Role of Remittances and Tourism

Worker remittances have long been a stabilising force in Sri Lanka’s external account. After a dip during the pandemic, inflows have rebounded strongly, reflecting both improved global labour conditions and better domestic FX management. These funds support household consumption, education, and small-scale investment but they are not a substitute for structural reform.

Tourism, too, is recovering, with arrivals climbing and revenue improving. However, the sector’s potential is constrained by outdated infrastructure, inconsistent service standards, and limited diversification. To compete with regional peers, Sri Lanka must invest in connectivity, digital marketing, and experience-based tourism that goes beyond beaches and heritage sites.

What Must Be Done

To convert recovery into durable growth, Sri Lanka must act on several fronts:

- Fiscal discipline with social protection

The government must maintain a credible path to primary surpluses while protecting vulnerable groups. This means targeted cash transfers, not blanket subsidies; rule-based pricing for fuel and electricity; and transparent budgeting that links spending to outcomes. - Investment in productivity

Growth must come from higher output per worker, not just more spending. This requires investment in agriculture modernisation, SME support, digital infrastructure, and vocational training aligned with market demand. - Regulatory clarity and investor confidence

Zones like Port City Colombo offer promise, but only if approvals are fast, transparent, and predictable. Publishing service-level metrics, codifying incentive governance, and showcasing real operating tenants will build credibility. - Export diversification

Sri Lanka’s export basket remains narrow. Expanding into IT services, high-value agriculture, and niche manufacturing can reduce vulnerability to commodity cycles and FX shocks. - Institutional reform

From SOEs to procurement systems, institutional efficiency must improve. Performance-based management, digital audits, and independent oversight can reduce leakages and restore public trust.

The Road Ahead

Sri Lanka’s economic trajectory is no longer in freefall but it is not yet on firm ground. The next 12–18 months will be decisive. If reforms continue, investment flows, and institutions deliver, the country can pivot from crisis management to growth strategy. If not, the recovery risks stalling, and the gains of 2024–2025 may prove temporary.

The crossroads is real. One path leads to resilience, competitiveness, and inclusive prosperity. The other loops back to fragility, populism, and missed opportunity. The choice is collective, and the time is now.