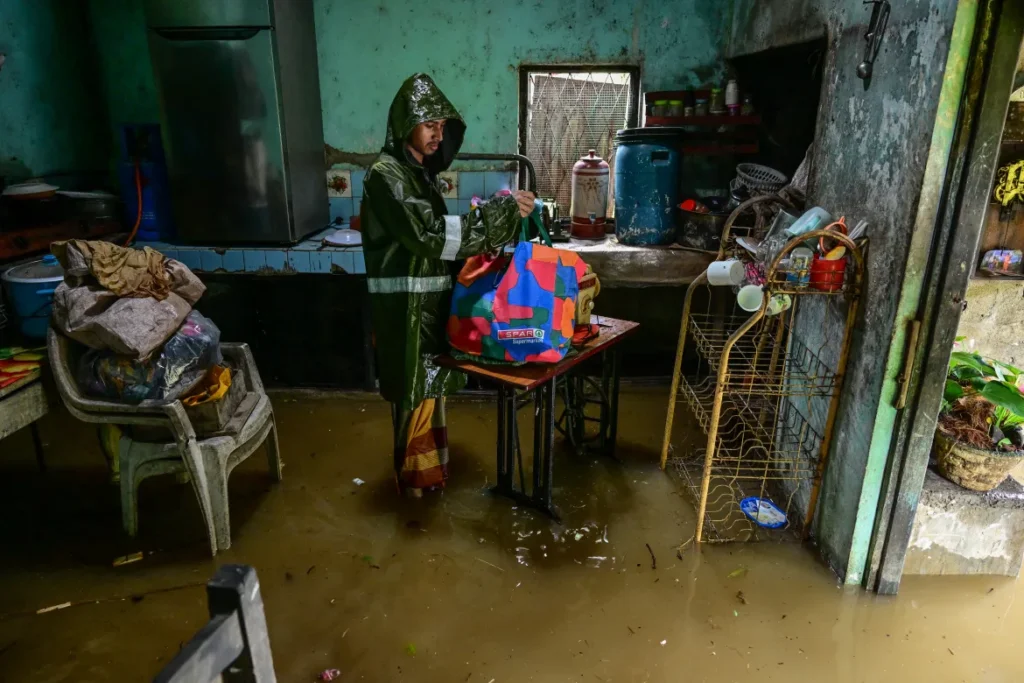

When a cyclone tears through a country, the immediate images are always the same; fallen trees, flooded homes, damaged roads, boats pushed inland, families sheltering in schools. But long after the water recedes and the news cycle shifts, the real recovery quietly begins in kitchens, shops, fields, classrooms, and tea stalls. It is a slow, uneven process shaped by how ordinary people rebuild their lives while navigating Sri Lanka’s already fragile socio-economic landscape.

For Sri Lanka, the latest cyclone struck at a time when households were still managing the aftershocks of economic crisis high living costs, unpredictable income streams, and reduced public services. Rebuilding therefore requires more than infrastructure repairs. It demands a people-centred approach that acknowledges the pressures individuals and communities face every single day.

This is the moment for policymakers, local authorities, and private-sector leaders to steer recovery with clarity, compassion, and long-term thinking.

1. The Everyday Realities Behind “Recovery”

For many families, the cyclone did not just damage property, it disrupted the delicate balance of survival. Households that were already stretching their budgets to afford electricity, transport, schoolbooks, or medication now face entirely new expenses: roof repairs, lost tools, damaged appliances, spoiled stock, and days of lost wages.

A vegetable seller whose stall was washed out may not have the capital to buy fresh produce the next day. A trishaw driver whose vehicle was flooded can’t earn until it is repaired. A fishing family that lost nets or boats may lose income for weeks. Daily-wage workers, who depend on consistent labour, lose earnings when roads are blocked or job sites are closed.

These everyday pressures rarely make headlines, but they determine whether communities recover quickly or remain trapped in debt cycles.

Sri Lanka’s recovery plan must acknowledge that disasters hit hardest in a context where:

- wages have not kept up with inflation,

- many households have depleted savings,

- small businesses rely on unstable incomes,

- and rural families depend heavily on climate-sensitive livelihoods.

It is in this context that recovery efforts must be designed.

2. Prioritising Livelihoods Alongside Infrastructure

Rebuilding roads, bridges, and power lines is essential but restoring incomes is equally critical.

Most small businesses and self-employed individuals do not have insurance, cash reserves, or access to rapid credit. Without targeted support, a temporary setback quickly becomes long-term economic hardship.

A strong livelihood-centred recovery should include:

- Micro-grants for small traders, fishers, farmers, and home-based entrepreneurs

Simple, fast disbursements even small amounts help families restart income-generating activities without sinking deeper into borrowing. - Concessionary loan restructuring

Banks and finance companies must offer grace periods and flexible repayment plans for cyclone-affected borrowers, especially in microfinance-heavy districts. - Rapid processing of insurance claims

Where insurance exists, delays deepen losses. A coordinated task force can accelerate verification and payouts. - Temporary public works programmes

Hiring local workers for cleanup, reconstruction, and community repairs injects income directly into affected areas.

Sri Lanka cannot afford a recovery that leaves informal workers behind. They form the backbone of the local economy.

3. Strengthening Social Support Systems During Crisis Recovery

A disaster exposes gaps that exist even in normal times: weak social safety nets, overstretched healthcare systems, and underfunded local authorities.

During cyclone recovery, the pressures intensify. Families face increased health risks from contaminated water, limited transport, rising food prices, and disruptions to schooling.

Three areas require immediate reinforcement:

- Health and wellbeing

Local clinics need resources to manage injuries, infections, and post-disaster stress. Mental health support especially for children, elderly people, and frontline workers should be integrated into community outreach, not treated as secondary.

- Education continuity

Flooded schools or damaged transport routes mean children miss classes. Temporary learning spaces and subsidised transport can prevent long-term academic setbacks.

- Food security

Cyclones disrupt supply chains and push prices up. For households already struggling, even a 10% increase in vegetables or rice is felt immediately. Food-support programmes, targeted vouchers, and community kitchens can stabilise vulnerable households during the first weeks of recovery.

These initiatives may seem small, but they significantly buffer households against financial shock.

4. A Recovery That Builds Climate Resilience

Sri Lanka cannot rebuild only to face the same devastation during the next storm. Climate events are becoming more intense and frequent. Recovery must therefore be both restorative and preventative.

Climate-resilient infrastructure

- Elevated roads and bridges

- Improved drainage in urban and semi-urban areas

- Cyclone-resistant roofing for schools, hospitals, and homes

- Strengthened coastal barriers and natural mangroves

Agricultural adaptation – Farmers need access to climate-resilient seeds, water-efficient irrigation, and timely agro-advisories. The agricultural sector cannot rely on pre-crisis methods when weather patterns are shifting unpredictably.

Urban planning and zoning enforcement – Settlements in flood-prone zones remain vulnerable. Local authorities must uphold zoning rules not only after disasters but during routine construction approvals.

5. Transparent Recovery Builds Public Trust

The public wants to see where funds go, how aid is distributed, and what progress has been made.

A transparent recovery framework should include:

- a publicly accessible district-level dashboard,

- regular updates from local authorities,

- independent audits of relief funds,

- and clear eligibility criteria for assistance.

Transparency is not administrative formality. It is a stabilising force in a country where economic hardship has already eroded trust in institutions.

6. Local Leadership and Community Networks

Communities often rebuild faster than governments neighbours sharing food, youth groups clearing roads, religious institutions sheltering families.

Recovery planning should empower these networks:

- Give community-based organisations micro-funds for local repair priorities.

- Train village response teams in first aid, basic engineering checks, and evacuation protocols.

- Strengthen Grama Niladhari coordination with local disaster-management units.

Local knowledge often determines which households are most vulnerable and which interventions are most urgent.

7. The Private Sector’s Role in Fast-Tracking Recovery

Corporates, SMEs, and industry groups are powerful accelerators of recovery when mobilised strategically.

Private sector contributions can include:

- logistics and transport for relief distribution,

- emergency credit lines and digital cash transfers,

- infrastructure material at concessionary rates,

- mobile clinics and technical support,

- and CSR-driven restoration projects.

Public–private coordination avoids duplication, reduces costs, and speeds implementation a necessity during national emergencies.

8. Rebuilding as an Economic Opportunity

Recovery is not only about fixing what was broken it is a chance to rethink regional development, strengthen climate preparedness, and modernise local economies.

Cyclone-hit regions can benefit from:

- new job creation through reconstruction,

- improved public infrastructure,

- digital payment expansion for small traders,

- diversified livelihoods in fishing and agriculture zones,

- and stronger integration into national supply chains.

If executed well, recovery can become a catalyst for long-term resilience.

Conclusion: Recovery Begins with Dignity

Cyclones damage structures, but they also disrupt lives. A recovery that focuses only on projects not people will deepen inequality and prolong hardship. Sri Lanka has an opportunity to rebuild quickly while addressing the socio-economic vulnerabilities that made communities so fragile to begin with.

True recovery begins when households regain stability, children return to school, small businesses reopen, and families can sleep without fear of the next storm.

Rebuilding must therefore be people-centred, climate-ready, and transparent the only path to a stronger, more resilient Sri Lanka.

Ceylon Public Affairs will continue to provide verified updates and policy analysis as the situation develops.

Read the previous analysis | After Cyclone Ditwah: What Sri Lanka’s Disaster Readiness Really Reveals

Read the related analysis | Rebuilding After the Cyclone: What Sri Lanka’s Economy Needs Now