Sri Lanka’s 1,340 km coastline is both a source of immense economic potential and a delicate ecological treasure. From pristine beaches and mangroves to coral reefs and estuaries, these ecosystems sustain fisheries, tourism, and coastal livelihoods(Coastal Ecosystems). At the same time, they provide vital natural defences against erosion, storm surges, and climate change impacts. However, rapid urbanisation, unchecked tourism infrastructure, and climate-driven changes are placing unprecedented strain on these fragile environments.

The Economic Pull of the Coastline

Coastal zones contribute significantly to Sri Lanka’s GDP. Tourism, much of which is concentrated along the coast, generated over US$1.8 billion in revenue in recent years before the pandemic downturn. Fishing communities along the east, south, and west coasts depend on nearshore ecosystems for daily sustenance and income. Ports and industrial zones in places like Hambantota and Colombo further highlight the economic gravity of coastal regions.

Development has the potential to uplift livelihoods, expand infrastructure, and boost exports. But without sustainable planning, these gains can come at an environmental cost that undermines long-term prosperity.

Pressures on Coastal Ecosystems

Several key threats are already eroding the resilience of Sri Lanka’s coastal habitats:

- Unregulated construction – Hotels, restaurants, and holiday homes often encroach into sensitive zones such as sand dunes and mangroves.

- Marine pollution – Plastic waste, oil spills, and untreated sewage degrade water quality and harm marine species.

- Climate change – Rising sea levels, coastal erosion, and saltwater intrusion threaten both ecosystems and human settlements.

- Coral reef decline – Coral bleaching events, driven by ocean warming, have already affected significant reef areas, reducing biodiversity and fisheries productivity.

- Overfishing – Excessive nearshore fishing disrupts the ecological balance, particularly when destructive practices like dynamite fishing are used.

Case Study: Mangrove Loss and Restoration

Sri Lanka has lost large swathes of mangroves over the last century, mainly to aquaculture, urbanisation, and tourism infrastructure. Yet, mangroves serve as critical nurseries for fish, stabilise shorelines, and act as carbon sinks. Encouragingly, community-led restoration efforts, supported by organisations like Seacology and local NGOs, have shown measurable success in replanting degraded areas and promoting sustainable livelihoods.

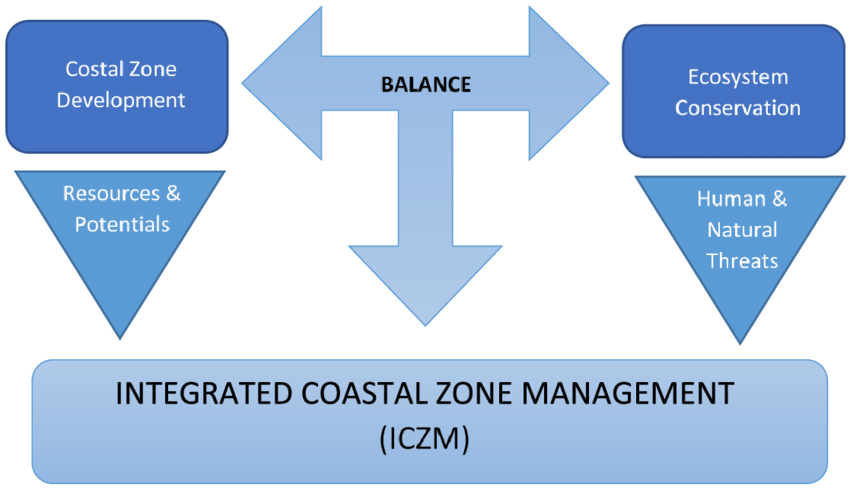

The Need for Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM)

Balancing development and conservation requires a framework that brings together all stakeholders—government agencies, local communities, private investors, and environmental experts. ICZM offers such an approach, ensuring that economic activities are planned in harmony with environmental limits. This means:

- Enforcing construction setback zones to prevent encroachment into vulnerable areas.

- Conducting mandatory Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs) for large-scale coastal projects.

- Incentivising eco-friendly tourism and fishing practices.

- Investing in research and monitoring to track ecosystem health.

The Role of Local Communities

Sustainable coastal management is not solely a matter for policymakers. Fishing villages, small businesses, and local tourism operators are on the frontlines of both the benefits and risks. Community-based conservation projects, such as turtle hatcheries in Rekawa or reef monitoring in Pigeon Island, demonstrate that local stewardship can make a measurable difference when supported with funding and technical expertise.

Policy and Enforcement Challenges

While Sri Lanka has regulations to protect coastal ecosystems—such as the Coast Conservation and Coastal Resource Management Act—weak enforcement remains a recurring challenge. Political pressure, bureaucratic delays, and limited resources for monitoring mean that violations often go unaddressed. Strengthening institutional capacity and ensuring accountability are key to closing this gap.

Global Lessons for Sri Lanka

Countries like the Philippines and Seychelles have pioneered marine protected areas (MPAs) that balance biodiversity conservation with controlled economic use. These models show that well-managed MPAs can increase fish stocks, enhance tourism revenue, and protect vulnerable habitats. Sri Lanka could adapt similar models, particularly in biodiversity hotspots such as the Bar Reef Marine Sanctuary and the Great Basses Reef.

Looking Ahead

The choice facing Sri Lanka is not between development and conservation—it is about integrating the two in a way that secures both ecological and economic resilience. This requires coordinated national policy, local participation, and a willingness to enforce environmental laws even when faced with short-term economic temptations.

If managed wisely, Sri Lanka’s coastal ecosystems can remain both a natural heritage and an economic engine for generations to come. If neglected, the cost will be borne not only by the environment but by the communities and industries that rely on it.